The Yahrzeit Project

December 29, 2022

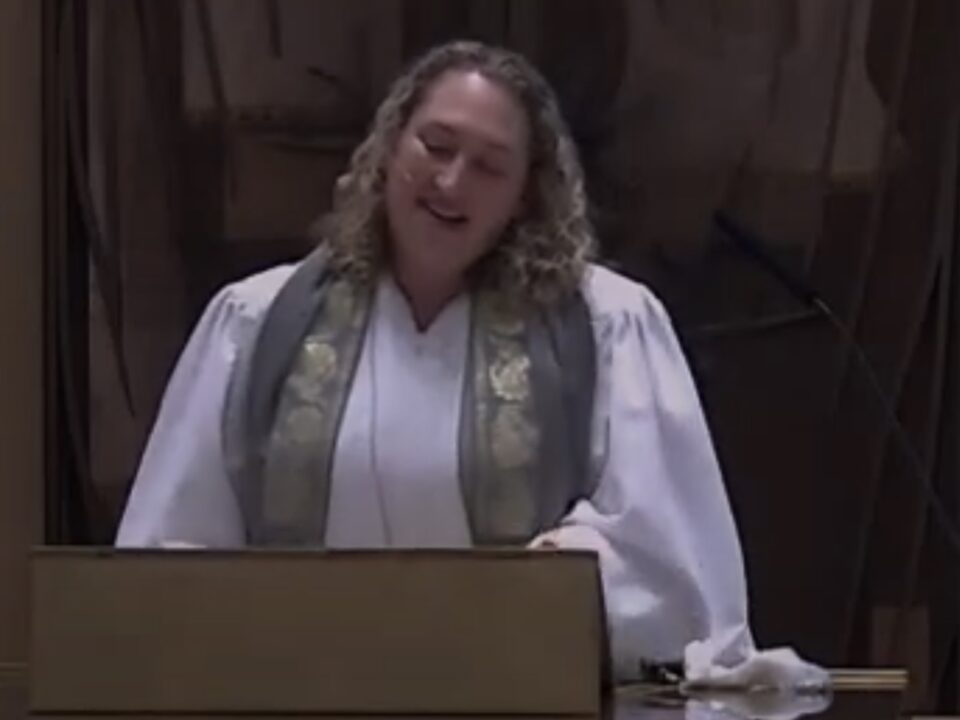

Rabbi Frankel’s Sermon for Yom Kippur, 5784/2023

September 29, 2023Hear the Shofar, Heed the Silence

Shabbat Shalom, Shanah Tovah. I hope the New Year is off to a sweet start, or as my favorite seasonal t-shirt reads: “Shofar Shogood!” All puns aside, the shofar is truly taking center stage in 5784 thanks to Cantor Oringel and our congregant Evan List, who have been training a cadre of new shofar blowers over the past few months. If you are inspired by their joyful noise tomorrow, perhaps you too would like to join their ranks, but don’t worry if not, because the mitzvah of shofar isn’t actually to blow it, but rather to HEAR it. The shofar blessing we say concludes “Lishmoa Kol Shofar” from the same root as Shema, to listen. Indeed hearing the sound of the shofar is the only biblical commandment specifically for Rosh Hashanah. While the later rabbis gave today that title “head of the year,” our Torah simply calls it Yom Teruah, a day of blasting.

This fall, I heard my first tekiya of the year at the most unexpected of sanctuaries– Madison Square Garden! Over Labor Day Weekend my husband, Andrew, and I joined some 15,000 other Jews at MSG to hear modern Orthodox Israeli pop star, Yishai Ribo, in concert. I had fallen in love with Ribo’s music last summer in Jerusalem so you can imagine both my delight and I must confess, shock, to hear he’d be performing his fusion of mizrahi, prayer-infused pop music in New York’s largest arena. That night MSG transformed into the most packed El Al flight ever, complete with multiple minyans davening alongside the kosher concession stands. The concert was pretty spectacular with tens of thousands of Jews across the denominations dancing and singing entirely in Hebrew. The music featured a full brass band, great percussion, and towards the top of the evening, the unmistakable sound of a ram’s horn. It was wild and awesome in the truest sense of the word.

So why do we blow the shofar? You won’t be surprised to hear that our Sages offer a range of answers; you know, two rabbis, three opinions! In one Talmudic tractate, Rabbi Abihu teaches: “The Holy One Blessed by God says, ‘Sound before Me a ram’s horn so that I may remember on your behalf the binding of Isaac, the son of Abraham, and account it to you as if you had been bound yourselves before Me.” An allusion to the Akedah which we will read tomorrow, the shofar takes us back in time, evoking our ancestors’ sacrifices and connecting us to a series of key biblical moments that we somehow simultaneously relive when we hear it. From the ram’s horn that caught Abraham’s eye just in time to spare his son, to the cacophonous shofar blasts at Mt. Sinai, and the steady blows that brought the walls of Jericho tumbling down, this ancient announcing tool wraps 3,000 years of Jewish history into a single sound.

Over the course of those three millenia, the significance of the shofar became ever more richly layered. For the medieval philosopher Maimonides, the shofar was meant to jar Jewish communities, to rouse us sinners from our slumber and trigger the process of Teshuvah. Still for many of us today, the shofar works like a spiritual alarm clock, calling us to attention and urging us to return to the right path, to renew ourselves in the year ahead. By contrast, for the Kabbalists, those 16th century hippie mystics, the sound of the shofar played almost the reverse role, blown to get God’s attention, not our own. They believed that on Rosh Hashanah, if we remind God of our covenant, then God’s commitment to creation would be renewed. How does one make sure God is noticing us? Blow a loud, stinky shofar towards heaven!

Each unique blast of the shofar is also rife with symbolism. The first tekiyah, which we heard just earlier, announces the New Year and declares God’s Sovereignty like the sound at a King’s coronation. The shevarim mimics a kind of mournful wailing, reminding us of those who suffer in our midst and articulating that which personally pains us. The frantic teruah urgently calls us to open our eyes and ears to the changes we need to make in ourselves and in the world. The Hassidic Master known as Degel Machaneh Ephraim suggested that this shofar blast in particular is meant to actually shatter our hearts, the first step towards an ethical reawakening.

Taken together, Rabbi Art Green articulates how the arc of these sounds might help move us through a process of cheshbon hanefesh or spiritual accounting: “Each series of shofar blasts begins with tekiyah, a whole sound. It is followed by shevarim, a tripartite broken sound whose very name means ‘breakings.’ ‘I started off whole,’ the shofar speech says, ‘and I became broken.’ Then follows a teruah, a staccato series of blast fragments, saying: ‘I was entirely smashed to pieces.’” But as Rabbi Green also notes, every set of shofar blasts must end with a tekiyah, pointing to the promise of renewed wholeness if we do the spiritual work of these High Holy Days.

Whether it’s here in the sanctuary, down in Manor Park, or even in Madison Square Garden, there is something so gripping, so primal about hearing the sound of the shofar that traditionally we spend the entire month of Elul tuning our ears for it. A single blast is blown each day leading up to Rosh Hashanah so that we are really ready to hear the 100 cumulative calls over the course of the holiday. But this year, as you may have heard, the majority of synagogues around the world will in fact be shofar-less tomorrow. Yes, Reform congregations like ours will include shofar anyway, however technically Jewish law explicitly forbids the blowing of shofar on the Sabbath, due to the prohibition on carrying objects among other halachic reasons. So for millions of fellow Jews tomorrow, it will be as if that spiritual alarm clock never goes off. Sitting instead in relative quiet, they will have to work even harder to crack open their own hearts.

Now let’s be honest: Jews are notoriously terrible at tolerating quiet let alone real silence. We are very good at kibbitzing, filling even the briefest of pauses with chatter. Even our “silent prayer” each Shabbat is usually quickly accompanied by some soft piano playing after no more than a minute. There is something uncomfortable and awkward for most people if silence lingers much longer and we are left alone with our thoughts. According to one recent study in Science Magazine, the majority of participants would rather receive small electric shocks than sit even for a few minutes in silence!

Maybe it is the vulnerability we feel in a prayer space when we set aside the psychological armor of music and words. It’s relatively easy, exciting even, to listen to the startling blasts of the shofar, but sitting quietly with our own thoughts can be so much harder. We don’t know what might bubble up inside us when we stray from our well-practiced liturgical script. Despite the insistence of Shel Silverstein’s upbeat poem, as we grow older it gets increasingly difficult to listen to that “Voice inside my head that whispers all day long.” But the longer we really lean into the silence, paradoxically, the more we start to hear. As Simon and Garfunkel taught us all, there can be so much calling out to us in “The Sound of Silence.”

I experienced this quite viscerally this summer, spending most of August sitting at my mother’s hospital bedside following the removal of a benign brain tumor and a series of subsequent complications. Especially during those early days in the ICU, when she was sleeping or sedated, her eerie quiet only underscored other sounds around me: the drip, drip, drip of her IVs, periodic beeping of the machine monitoring her vitals, and thank goodness only briefly, the buzz of a life-sustaining ventilator.

In hearing THESE sounds, I became more attuned to the mysterious and oh so tenuous gift of life. When I couldn’t hear my mom’s voice, I sought out human connection in the countless doctors, nurses, physicians assistants and therapists who cycled through her room and saved her life. And the longer I sat there quietly praying for her recovery, the more I began to notice the other ICU patients too and started adding them to my Mi Shebeirachs–these total strangers whose names I didn’t know but whose lives also hung in the balance and whose struggling bodies contained the same Divine spark as my mom’s. (I am tremendously grateful to sidenote that after nearly five weeks at Columbia Presbyterian hospital; she graduated today and was moved this very evening to rehab.)

On a societal level, the same phenomenon of more clearly tuning in occurs when we cut through the constant clamor of partisan politics, quiet some of the steady stream of noise around us and really listen to those around us. If we can silence ourselves, we start to hear the sounds of our neighbors suffering, the marginalized voices–of women, people of color, immigrants, members of the LGBTQ community–and the subtler injustices they endure daily. It’s true, the loud shofar blasts might call us to do acts of holy healing, but first we must really hear those whose cries are so often stifled or never heard at all.

Back in March, I had an experience of such soul-shaking, heart-breaking silence down in Montgomery, Alabama. Representing our Westchester Board of Rabbis, I joined an interfaith clergy group, along with Strait Gate’s youth minister Tiffini Thrower, to participate in a Civil Rights Journey, run by an organization called Etgar 36 and funded by the UJA-Federation of New York. Over these few jam-packed days, we learned more of the nuanced details of events we’d studied only on a surface level in our youth, to visit historic sites in the fights for Civil Rights and even heard from surviving participants in those watershed moments. We stood at the Montgomery street corner where Rosa Parks boarded that bus and even walked across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, following in the footsteps of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel after “Bloody Sunday.”

But there was one place on our trip that left us simply speechless. The National Memorial for Peace and Justice is a six-acre site in Montgomery memorializing victims of racial terror in the US between 1877 and 1950 through a breathtaking combination of sculpture, visual art, and architecture. Spiraling around a central courtyard, 4,400 names of lynching victims are inscribed in steel pilasters that look at first like grounded tombstones but slowly rise until they are hanging high overhead, a chilling allusion to brutal deaths of these innocent men, women, and children of color.

This was the one place we toured that wasn’t a group walk and talk; rather, we were instructed by our leader, Billy Planer, to silently and individually make our way through the maze of names until we reached the center clearing–a hint, it was explained, at the way in which most of these brutal murders took place in broad daylight in public view. Words cannot adequately capture the experience of quietly wandering through those thousands of names of lynching victims, confronted by both the scale of such human horror and the reminder of how many people stood idly by during each of these murders. My rabbinic colleagues and I could only really begin to process it all through the lens of having visited Yad Vashem and other Holocaust memorials. It was that familiar “Never Again,” but also completely foreign and new to us.

Like so much of the violence against our own people, much of what we heard about on that Civil Rights trip were quiet tragedies and torture endured by the African American community that no one even ever speaks of, the scope of which even we religious leaders were shamefully unaware. No one is blowing shofars or blasting proverbial sirens to draw our attention to these dark chapters of American history or the ways in which systemic racism still very much exists in our broken criminal justice system. Yet we needed to hear it all, to keep quietly listening even when we felt uncomfortable or embarrassed, in order to return home to Westchester and work together to build bridges across religious and racial lines. To get back to that strong and unbroken collective tekiyah.

At the hospital with my mom and down in Alabama with cherished clergy colleagues, I learned that precisely when we listen, really listen, to our own inner conscience or to the suffering of another, that we might also merit hearing that Divine whisper we seek on this day. The Book of Kings recounts a story of God calling the prophet Elijah out of a cave to stand upon a mountaintop and meet his Maker. “There was a great and mighty wind,” we read, “splitting mountains and shattering rocks by the power of the Eternal; but God was not in the wind. After the wind–an earthquake, but God was not in the earthquake. After the earthquake–fire, but God was not in the fire. And after the fire, a soft murmuring sound–kol d’mamah dakah, or as Rabbi Jonathan Sacks translated it, “the sound of slender silence.” THERE, our tradition teaches us, is where Elijah finally heard God’s voice.

So too, I hope for all of us over these next ten days. To be sure, these High Holy Days will be a feast for our ears: from those soul-stirring blasts of the shofar, to the joyful and harmonious singing of our Cantor and choirs, to the voices of generations of LT-ers chanting Torah and schmoozing. But may we also find for ourselves some moments of intentional quiet, even that uncomfortable, humbling, hard silence to simply listen–for the hopes in our hearts, the heartache of others and that Divine whisper calling each of us to grow.

L’Shanah Tovah U’Metukah. May it be a sweet, healthy, and happy New Year for us all.