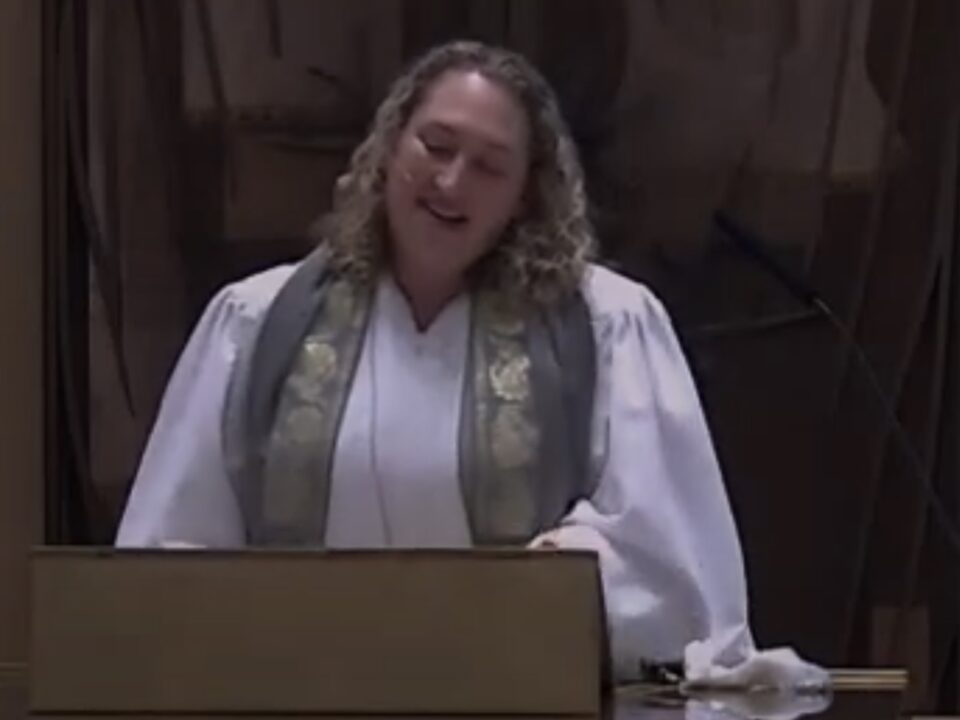

Rabbi Sirkman’s Sermon for Rosh Hashanah, 5783/2022

September 29, 2022

Rabbi Sirkman’s Sermon for Kol Nidre, 5783/2022

October 6, 2022Made of Star Stuff: The Webb Telescope and our World of Obligation Erev Rosh Hashanah 5783 Sermon

A psalm of David.

The heavens declare the glory of God, the sky proclaims God’s handiwork. Day to day makes utterance,

night to night speaks out.

There is no utterance,

there are no words,

whose sound goes unheard. [i]

These lines from Psalm 19 came to mind this past July when the first Webb telescope photos were released by NASA at that dramatic press conference. I was in Jerusalem, surrounded by 175 other rabbis all studying at the Shalom Hartman Institute for two weeks. I’ll share much more about the conference learning tomorrow afternoon, but Hartman meals were a chance to network, discuss our thoughts on the latest lecture, and sneak a peek at our e-mail. So at dinner that Tuesday night, when a colleague at the next table exclaimed “Whoa!” I assumed she’d had some great Talmudic insight or received an important message from a congregant back home. But then there was an adjacent “Wow!” and a nearby gasp and (in full transparency) some other expletives that I shouldn’t quote rabbis blurting out while speaking from the bima. Within a couple of minutes, the murmurs crescendo-ed while we all opened our respective news apps to look at this never-before-seen image. [slide 1- see Appendix]

As I’m sure so many of you found when viewing those five initial pictures from the Webb press conference, or with the earlier Hubble broadcasts, I was simply speechless at first. The photos were too exquisite to even feel real. Once the initial shock wore off, I remember whispering the Shehechiyanu blessing as we all internalized the magnitude of this historic moment—equal parts scientific and spiritual. And as I read more about these breathtaking views of our universe and what they represented, it began to sink in that somehow we were not only looking far out into space, but also way back in time.

Before ever seeing these summer snapshots, the story of the Webb telescope was already pretty amazing. Named after the 1960s NASA administrator James Webb, [ii] this much-anticipated successor to the Hubble represents a culmination of 30 years and $10 billion worth of research and engineering. Without getting too mired in the technical details (clearly above my rabbinic pay grade), the Webb has several times more power than the Hubble to see the universe’s earliest stars with its camera’s unique infrared sensitivity. This feature allows astronomers to penetrate through dust clouds and detect wavelengths that are normally invisible to the human eye. The results, they hope, will provide clues as to how and when the oldest stars were formed after the Big Bang, why black holes develop, and even search the atmospheres of other planets for signs of life. [iii] Quite literally, the Webb telescope is enabling us to gaze at “a galaxy far, far away,” and at the same time, to better understand the creation our world.

With so much hype and audacious hopes loaded on that shuttle, the reality of the Webb telescope might have disappointed. In the end though, it has far exceeded everyone’s expectations. When deployed, it was designed to carry enough fuel to last for a 10-year mission, but NASA has since announced that the flawless Christmas morning launch actually left it with enough propellant to double the length of its operation. In nearly every other realm too, the Webb seems to be outperforming its design specs with sharper optics, more precise guidance, and more sensitive instruments than NASA had even predicted. [iv]

Just as impressive is the international collaboration that went into the Webb telescope’s design. Against the backdrop of an increasingly siloed world, the telescope is the result of a global partnership between NASA, the Canadian and European space agencies. Together they engaged some 20,000 astronomers, technicians, and programmers like Lockheed Martin software engineer Dan Lewis, who spent the past sixteen years working on the Webb’s infrared camera. [v]

Or Dr. Jane Rigby, a 43-year-old astrophysicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center who serves as the agency’s operations project scientist and was bestowed the 2022 LGBTQ+ Scientist of the Year by Out to Innovate. [vi] Among her responsibilities is to help craft the itinerary for the Webb telescope, taking into account the astronomers’ various targets, the best times and conditions for observing them, and the rate that data can then get relayed back to earth. [vii] (Her job gives new meaning to the old folk song, “She’s got the whole world in her hands...!)

Despite supply chain shortages, a pandemic, and raging war in Ukraine these recent months, the Webb embodies the positive potential of nations coming together to dream and build and discover. Thanks to decades of dedication by so many more talented individuals, we all were invited this summer to celebrate this triumph of the human spirit, witnessing those first telescope images with a sense of collective wonder. One of those inaugural photos was Stephan’s Quintet, [slide 2] a cluster of five galaxies billions of light years away, four of which pull and tug on each others’ gravities in a delicate dance the Webb allowed us to glimpse. Then there was the spectacular Southern Ring Nebula [slide 3], a detailed image of a dying star losing emitting successive shells of dust and light. Like the oft-quoted Hannah Senesh poem about the brightest stars whose light shines long after the star itself is gone, [viii] the Southern Ring Nebula’s outer glow ever increases as the star in its center slowly fades away. [ix]

Finally, my favorite Webb photo so far is this one of the Carina Nebula [slide 4], a vast swirling cloud of dust and “home to some of the most luminous and explosive stars in the Milky Way. Seen in infrared, the nebula resembled a looming, eroded coastal cliff dotted with hundreds of stars that astronomers had never seen before.” [x] Looking at the cosmic cliffs of the Carina Nebula is pretty mind-blowing (don’t you think?), especially when reminded of astronomer Carl Sagan’s famous quip: “The cosmos is within us. We are made of star stuff.” He was not speaking in hyperbole; we really are comprised of those very same elements—carbon and hydrogen and oxygen—as the stars we’re staring at. [xi] Our Torah adds however, that each of us is also imbued with a divine spark which shines within, like those luminous lights across the cosmos. [xii]

Seeing these pictures reminded me how wholly compatible, even inextricably bound, science and spirituality can be. My own young children seem to experience intuitively. This summer at Manor Beach, my 6-going-on-16-year-old Judith, peppered me with the endless questions and an accompanying sense of amazement at the mysterious beauty around us: “Mommy, why is the water sometimes so high and other times so low? How did some of those big rocks become tiny grains of sand? Could we count them all?” And on and on. The kids and I would spend hours at our little Sound Shore oasis, marveling at the mysterious miracles we could see and touch, though never fully grasp. Then we’d pile into the minivan to head home, covered head to toe in sand and glowing with gratitude.

In his iconic work Man is Not Alone, Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel wrote, “Sometimes we wish the world could cry and tell us about that which made it pregnant with fear-filling grandeur. Sometimes we wish our own heart would speak of that which made it heavy with wonder.” [xiii] For us adults too, is often an encounter with the natural world that most stirs in us the sense of awe Heschel describes. With all due respect to our clergy team and this special sanctuary, by show of hands, how many of you feel most deeply spiritual out on a forest trail (with Jim Cowen) or deep in the desert. When we stare up at a starry sky on a clear night, even without the aid of the Webb telescope, it is impossible not to contemplate the universe’s interconnectedness and the possibility of a pervasive power that runs through it all. Some of us, including Heschel’s rabbinic buddy Mordechai Kaplan, might even call that force itself God.

But the Webb photos can evoke two potentially opposite spiritual responses, like the beloved Simcha Bunim teaching personified. The Chassidic master advised us to always keep a note in one pocket reading, “I am but dust and ashes.” [xiv] These overwhelming pictures of the cosmos might make us feel very small and insignificant in the grand scheme of it all. Albert Einstein expressed such a sentiment in a little-known letter he wrote to Rabbi Dr. Robert Marcus in 1950 who reached out seeking comfort after the tragic death of his son. In his response to Marcus, Einstein reflected, “A human being is part of the whole, called by us ‘Universe,’ a part limited in time and space. He experiences himself, his thoughts and feelings as something separated from the rest — a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness.” [xv] Sounding as much like a Jewish mystic as an atheist physicist, Einstein scoffed at humanity’s hubris in envisioning ourselves to have some elevated place above the rest of the universe of which we are a part.

But you could also turn this observation on its very head and think instead: “In this inexhaustible vacuum of emptiness, with its extreme hostility to life, how could the astounding perfection of our world’s capacity to host us be any more remarkable?” [xvi] What an unlikely and unique gift this life on Earth is—a miracle only fully appreciated perhaps when looked at from the vantage of a million miles away. For remember the note Simcha Bunim urges us to keep a note in other pocket too, one that reads: “The world was created for my sake.” [xvii] Glimpsing these far-flung galaxies we might indeed seem small but we also ought to feel inspired if not empowered. We might even imagine that looking at the Webb photos is like seeing the universe through the eyes of God. [xviii]

More than anything, just as the Webb offers us a deeper appreciation for both the universe and our role in it, the experience of seeing these pictures also obligates us in a new way. Rabbi Bradley Artson articulates in his book on Process Theology: “We are at once a part of creation, nestled within nature as a whole. And we are conscious of our place in nature and self- conscious at a level that may well be unique. We are called, therefore, to be nature’s voice and conscience, to sing its songs and to safeguard its vitality.” [xix] Being so deeply moved by these closeups of the stars, or simply witnessing a brilliant sunset, the tides at Manor Beach, or flora and fauna of the Leatherstocking Trail, must also lead us to a sense of sacred responsibility. To be Jewish is not just to pray with our minds and hearts, but also with our hands and feet, as Heschel himself modeled.

So consider this your personal invitation to join our LT Social Justice group in the Climate Covenant campaign of the Religious Action Center of Reform Judaism—a “covenant to act collectively across our movement and join with others across lines of race, faith, and class to end our dependence on fossil fuels and stop climate change.” [xx] One simple and concrete act of environmental stewardship you can take right away on November 8th. This election day, make sure to turn over your ballot to vote for New York’s Environment and Climate Change Projects Bond Measure. Passage of this proposal would issue 4.2 billion dollars for projects related to the environment, natural resources, climate change mitigation, and water infrastructure, something we learned all too well during Ida is lacking in our flood-prone area. To be clear, this is not a partisan political issue and there is no expected opposition to the bond; it is more of a technical concern. Unless people know to flip to the backside of their ballot, the requisite majority might not be reached. So don’t forget to fill out both sides of yours and help our Temple’s Green Committee spread the word.

Knowing that we are all made of the same star stuff, being fellow travelers orbiting the sun, also obligates us to one another. No matter our race, sexual orientation, or country of birth, our sacred sources affirm that the soul of every person is a Divine flame. [xxi] Our Talmud also teaches that each human life is like an entire world unto itself. [xxii] When children are gunned down in school, those kids are not just tragic statistics, but precious worlds snuffed out just as they were beginning to discover the power of their own light. And when we help to save a life, perhaps of a Ukrainian refugee who inexplicably landed in Larchmont, or to another stranger through donating blood or food, time or money, we are enlivening a whole universe.

On Rosh Hashanah morning we respond to the sound of the shofar with the words “Hayom Harat Olam- today the world is born or, maybe more accurately, re-conceived.” [xxiii] Our liturgy beckons us back to the beginning of time, to a brand new universe unfurled before us. And at the same time, we are called to attention by the demands of the present moment—Hayom, today. What will we do with this clean slate of our New Year? What positive difference can we make in another’s life or for our planet?

Radical perspective. Utter awe and deep gratitude. Peering out into the distant unknown and in so doing coming to better understand and appreciate our past. All these experiences are also an apt metaphor for what we are doing here over these High Holy Days. And, they are not limited to these ten days a year. I’ll let you in on a little secret: you don’t actually need a fancy telescope or the Jewish New Year to see the world as if from the Webb. Each and every day, our tradition invites us to wake up with wonder and make the most of our small but mighty place in creation’s endless unfolding. May we all strive to do so in 5783. Shanah Tovah U’Metukah.

Appendix of NASA Images [projected on sanctuary screens during sermon]

Webb’s first deep field image, showing the galaxy cluster SMACS 0723

Webb’s first deep field image, showing the galaxy cluster SMACS 0723

Stephan’s Quintet

Stephan’s Quintet

Southern Ring Nebula

The Carina Nebula

The Carina Nebula

i Psalm 19:1-4, adapted translation

ii https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/12/science/who-was-james-webb.html

iii https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/25/science/james-webb-telescope-launch.html

iv https://www.stsci.edu/files/live/sites/www/files/home/jwst/documentation/_documents/jwst-science- performance-report.pdf

v https://www.cbsnews.com/sanfrancisco/video/meet-scientists-who-built-the-james-webb-space-telescope- sending-images-of-deep-space/

vi https://www.nasa.gov/feature/goddard/2022/nasa-goddard-astrophysicist-awarded-2022-lgbtq-scientist-of-the- year

vii https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/meet-the-woman-who-makes-the-james-webb-space-telescope- work/

viii You can read the full poem here: https://ritualwell.org/ritual/yesh-kokhavim-there-are-stars/

ix https://www.nasa.gov/image-feature/goddard/2022/nasa-s-webb-captures-dying-star-s-final-performance-in- fine-detail

x https://www.nytimes.com/article/nasa-webb-telescope-images-galaxies.html

xi https://astrobiology.nasa.gov/education/alp/are-we-really-made-of-star-stuff/

xii Each creation narrative, in both Genesis 1 and 2, offers a version of this.

xiii Heschel, Rabbi Abraham Joshua. Man Is Not Alone (1951)

xiv Genesis 18:27

xv Levy, Naomi. Einstein and the Rabbi: Searching for the Soul (2017)

xvi Rabbi Adam Jacobs, Jewish Living Delaware blog

xvii Talmud, Sanhedrin 37b

xviii https://www.jta.org/2022/07/18/opinion/the-james-webb-telescope-looks-at-the-universe-through-the-eyes- of-god

xix Artson, Rabbi Bradley Shavit. Renewing the Process of Creation: A Jewish Integration of Science and Spirit (2016) xx https://rac.org/take-action/rac-your-state/rac-ny/rac-ny-launches-climate-covenant-rac-ny-campaign-combat- climate-change

xxi Proverbs 20:27

xxii Talmud, Sanhedrin 37a

xxiii Mishkan HaNefesh Machzor, CCAR Press

10