Rabbi Sirkman’s Sermon for Yom Kippur, 5783/2022

October 10, 2022

The Yahrzeit Project

December 29, 2022The Troubled Committed: Staying in Love With Israel

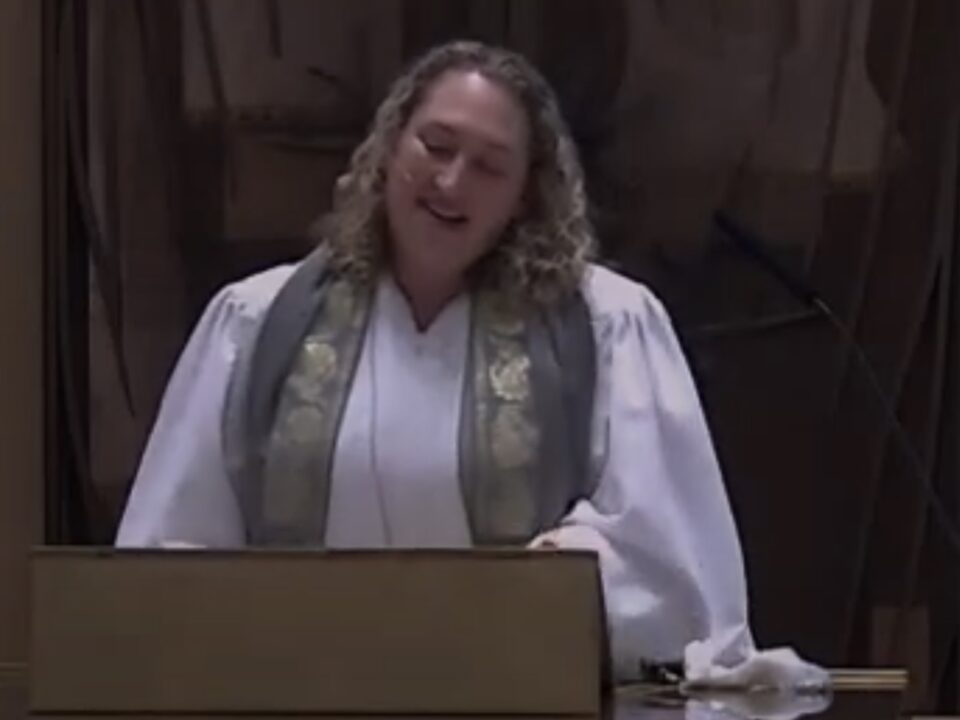

Rabbi Leora J Frankel, Larchmont Temple

Yom Kippur 5783 Tent of Meeting Service

There is nothing like a summer Kabbalat Shabbat at Tel Aviv port. Sun sinking straight into the sea as the waves break to the rhythms of L’cha Dodi. Though both sides of the prayerbook are in Hebrew, it’s an international crowd that has gathered to escort in the Sabbath bride with song and dance: secular and observant Israelis, North and South American tourist groups, folks just walking along the beach boardwalk who hear the music and wander over to have a closer view of the pop-up band belting out ancient prayers to modern tunes. And all this just 100 miles away from where the very psalms we’re singing were first written centuries earlier. Each time I experience that special Tel Aviv Kabbalat Shabbat service, I am moved to tears.

This past July was no exception, when after four long years away, I finally made it back home to Israel. Together with 175 other rabbis from across the denominational spectrum and around the world, I had the privilege of studying for 10 days at the Shalom Hartman Institute in Jerusalem. Founded in 1976 by Rabbi Professor David Hartman, the Hartman Institute runs an array of outstanding educational programs for both Americans and Israelis, including podcast and video lecture series, ethical leadership training for IDF generals, and several interfaith initiatives with Jews and Muslims living here, in Israel, and Palestine. The Institute is a unique amalgam of a think tank, Beit Midrash, and center for leadership development. But (COVID notwithstanding), for two weeks every July, the Hartman Jerusalem campus becomes what my colleagues and I affectionately call “Summer Camp for Rabbis.”

The Rabbinic Torah Seminar, or RTS for short, brings together clergy to explore contemporary issues facing the Jewish people through transformative learning with top Israeli and American Jewish scholars. Each morning we spend in lectures and small group hevruta study with the guidance of a master teacher from Hartman’s faculty. Afternoons are filled with elective Judaica classes, professional peer workshops, and just enough time to duck out to Ben Yehudah Street or the Shuk for a little shopping and shawarma. Then we gather again in the evening to hear panels of Israeli public figures and policy makers, or for a concert. Hartman RTS is intellectually rigorous and spiritually renewing, pushing us to reconsider texts and ideological tenets we rabbis think we know.

This summer’s RTS program revolved around a deceptively simple question: “Why Israel?”

Having grown up in the Zionist Youth Movement Young Judaea, the child of YJ sweethearts, it’s a question that I—and I’m guessing most of you—don’t even much consider. Israel’s centrality to my own family’s Jewish identity and to our collective story as a people is something I’ve long taken for granted. While my fellow 90s teens were off at camp playing capture the flag or steal the bacon, at Camp Tel Yehudah our favorite evening program was Choma U’migdal, a dramatic reenactment of the early pioneers’ middle-of-the-night race to build towers and stockades during the 1930s British Mandate Palestine. (It’s true, just ask Rabbi Sirkman who did the same as a camper at TY in the 70s; we couldn’t make this stuff up!)

Instead of campfire singalongs and dances to American pop tunes, we would spend hours each week singing old Israeli folk songs about the beauty of the land and do classic Israeli dancing until our feet fell off! At TY, we ate in the chadar ochel, gathered in the Beit Am… everything was in Hebrew, and half of our counselors were recent graduates of the Israeli army. It was basically little Israel along the banks of the Delaware river and it was magical.

By college, I had been on several trips and participated in Young Judaea’s gap year in Israel program studying and volunteering for 10 months after high school graduation. “Why Israel?” wasn’t even a relevant question, for nearly every year was a fulfillment of that closing Seder line “Next Year in Jerusalem.” So when Donniel Hartman posed that question “Why Israel?” to a room full of frequent visitors to Israel like myself, we were initially confounded. But we quickly understood that the question wasn’t really for us. For these 10 days, our rabbinic cohort was a proxy for the wider community of the North American Jewry—some affiliated with our synagogues, many more institutionally unengaged—and an increasing number we know are feeling deeply disaffected by if not entirely disconnected from Israel these days.

While the 2020 Pew study reported that 6 out of 10 American Jews do still feel an emotional attachment to Israel, once you take out the Orthodox community and non-Orthodox Jews above age 60, that statistic goes way down. In fact, nearly every index measuring connection to Israel in the research shows the numbers precipitously drop for each subsequent generation. Unless they have gone on Birthright, and often even still, more liberal Jews in their 20s and 30s are far less comfortable calling themselves Zionists than I was at those ages. Because let’s face it: it is neither popular nor easy to love Israel as a young person today, especially if you consider yourself to be at all progressive in other realms of your life.

This is not only because of the rampant BDS movement on college campuses or Israel’s bad press in the media, though these things certainly do not help. But the situation we find ourselves in is also because of how factions of our own Jewish community are also limiting the conversation about Israel or forcing upon us false dichotomies.

The newly released American Jewish Committee survey depicted a millennial generation that worries they must choose between affiliation with Israel and social acceptance. To say it more starkly, it’s hard for young Jews today to feel, let alone express aloud, any allegiance to Israel for fear of being labeled an enabler of Israeli Occupation or a sympathizer of an Apartheid State. And I should note here: we rabbis spent a lot of time at Hartman hearing and saying those uncomfortable phrases, whether or not we personally believe they are factually accurate. Because while some of us may find them objectionable or outright untrue, just dismissing these claims when we hear them or shutting down dialogue because of one word doesn’t do us or Israel any favors. And our young people—some of your children and grandchildren—are on the front lines.

For all the counter facts and figures we might debate about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, one thing is undeniable: loving Israel today is much harder than it used to be, especially if you don’t have those foundational firsthand memories or relationships there. When the Israeli government or its private citizens take actions that we deem immoral, not in line with our Jewish values, it becomes so hard to know how to even talk about it sometimes that we’re more likely to say nothing at all.

In the 50s and 60s, even the 1990s, it was much easier to wax poetic about the Promised Land and defend its every decision. We could unapologetically root for the underdog, always on the brink of existential threat. For we had witnessed with wonder as the Jewish people rose up from the ashes of the Holocaust not only to make a desert bloom, but to become the “Start Up Nation” whose technological innovation gave the world cell phones, instant messenger, Waze, and so much life-saving medical technology. And for all its cutting edge contemporary achievements, there was, there IS, something so transporting about touching the ancient stones of the Western wall or sitting in the Roman amphitheater in Caesarea. How could you not fall in love with Israel?

But as with all romantic relationships, staying in love over the long haul and through the decades is harder and more complicated than a brief if passionate fling. (I don’t have to tell anyone who’s been married for a decade or more!) Over the years we increasingly see our partner’s shortcomings as we have a front row seat to watch the inevitable mistakes they make, the many ways they fail to live up to our hopes or fantasies. We become so attuned to the parts of them that disappoint us that we lose sight of the many special qualities that attracted us in the first place. Sometimes, sadly, that can lead to divorce or at least a cooling of initial passion a couple shared. I’m not sure the opposite approach is any better though, a kind of feigned ignorance if our spouse is doing something truly wrong, because, well… we love them so how bad could it be?

A healthy reality, of course, lies somewhere in the middle, and so too with Israel. Yet the middle, or a space where we can simultaneously hold multiple truths, seems to be disappearing. Daniel Sokatch, CEO of the New Israel Fund articulates this powerfully in his new book Can We Talk About Israel: A Guide for the Curious, Confused, and Conflicted. Sokatch observes how “many otherwise intelligent people make the case ‘for Israel’ or ‘for Palestine,’ but only tell part of the story. They don’t acknowledge or genuinely see, that Israelis and Palestinians are both right and both wrong—that they are both victims of forces beyond their control, of each other, and of themselves.”

As with so many other dimensions of public discourse in this country, rhetoric around the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has become so polarized, insisting that we must make impossible choices: Either we can love and support Israel OR we can care about the suffering of Palestinians; we can invest in the continuity of a Jewish state OR we can stand up for human rights and the dignity of all people. We feel pressure from both within and outside the Jewish community to take a strong stand on one political extreme or the other when it comes to Israel, and in the end, everybody loses.

The goal, as Donniel Hartman puts it, is to join the ranks of Israel’s “troubled committed.” As he explains, one can be a longtime lover of Israel, but if you are not troubled by the ways Israel has started to use its hard-earned power to now subjugate others, then you are not truly invested in Israel’s long-term and full flourishing. For Israel’s Declaration of Independence commits to “ensure complete equality of social and political rights to all its inhabitants irrespective of religion, race or sex.” Alas, as one of the Hartman scholars pointed out this summer, if this document were to be brought to today’s Knesset floor, it would never pass, and not only because of discrimination against Arabs in Israel.

As a female, Reform rabbi, I am most definitely not treated as an equal to Orthodox men in Israel. Every time I visit the Kotel, especially when I’ve prayed there with Women of the Wall, I am infuriatingly reminded of the many ways I would be a second-class citizen in Israel as a progressive woman, even rabbi. But after being so frustrated by Israel’s religious hegemony to even set foot there on my prior is couple of trips, this summer, I forced myself back to the old city and made it up to touch those stones again where my ancestors have stood and prayed and wept for centuries. You can bet I felt troubled making my way past the hareidi women guarding their section from we heathen Reform Jews. But I realized that the alternative—walking away, ceding that sacred ground—just isn’t an option. I can’t stay in the fight for an egalitarian prayer space at the Western Wall if I never go there myself anymore.

As Donniel pointed out this summer, being so troubled by some aspects of Israeli politics that we just abandon it is no more praiseworthy than being committed with no conscience. Being among the “troubled committed,” or as some of us would say a liberal Zionist today may be lonely, but the real danger is in giving up on Israel all together because it is too frustrating or disappointing or exhausting trying to stay in relationship with a country that is indeed imperfect. (The very same, I might add, can be said of America these days, but alas, that is another sermon.)

This summer marked 125 years since the first Zionist Congress in Basel, Switzerland. Back in 1897 Theodor Herzl, proposing the establishment of a sovereign Jewish state, spoke those famous words, Im Tirtzu Ein Zo Agada- “If you will it, it is no dream.” And amazingly, Israel is real, no longer just a poetic longing in our liturgy, but a beautiful, vibrant, and complicated real country. Being among the troubled committed, or as Hartman’s US President Yehuda Kurtzer puts it, being an aspirational Zionist today, means that we need to keep dreaming about and for Israel, to support Israel’s striving to become the best possible version of itself… just as we are all personally doing here with the spiritual work of Yom Kippur.

Being the troubled committed demands that we look at Israel not just through the rose-colored glasses of a newlywed, but with more mature, discerning eyes. That we talk about the extraordinary, if still tenuous power Israel does finally have today, and how she wields it. It means reckoning with how the mythic stories of the nation’s founding were missing certain chapters and working towards restorative justice for those Arabs who were displaced by the Nakba even as we wholeheartedly defend Israel’s right to exist and be free of terror.

It means proudly using the “Z-word” as McGill history Professor Gil Troy calls Zionism, AND also affirming, as Rabbi Jill Jacobs does, that it is not inherently anti-Zionist or anti-Semitic to criticize Israel, especially if we do so from a place of sincere love. We can advocate for the increased funding of Israel’s defense system, fight for its secure borders AND still push its government and citizens to keep aspiring to the democratic principles in its Declaration of Independence. And no matter what Tamika Mallory or any other popular activist says, we can show up in the American public square and speak out on issues we are passionate about—from women’s reproductive rights to immigration, criminal justice reform and the environment—without checking our love for Israel at the door.

Like Israel itself, we are all multi-dimensional and complex, still growing and changing, recognizing our missteps and mistakes as we age, more fully seeing and understanding earlier chapters in our lives only from hindsight. And the people who love us most—our spouses, parents, children, dear friends—are also the ones most likely to help us transform our flaws and foibles for the better. If that’s not what today is all about, then I don’t know why any of us are even here!

For me, the answers to “Why Israel?” are far too many to share and still get us to Yizkor on time. But I’ll name just a few: I love Israel because it is the one place in the world where I can order my morning coffee and don’t have to use a Starbucks alias like “Laura” to know they’ll spell it right. (Shh- Don’t tell the local baristas when you see me in town that’s not actually my name.) Because Israel is the only place on earth where I can duck into dozens of shops to try out blowing their shofars (often startling my fellow shoppers) before finally selecting the one you heard blown here on Rosh Hashanah last week. Israel matters to me because it is the only place in the world whose soldiers have Jewish stars emblazoned on their uniforms, where Hebrew is rapped on the radio or used to call scores at sports games. Because it’s Rak B’Yisrael, only in Israel, that an Israeli cab driver feels like family after sharing a ride…and they probably are.

So at this season of turning and returning, with COVID becoming at least endemic, I hope that you will join our LT clergy in getting back to Israel as I had the gift of doing this summer, in person if you’re able. In February, we’ll finally hold our twice postponed family B’nai Mitzvah trip again, and hopefully next year a new adult one exploring art, culture, and cuisine. As I was reminded yet again in July, there is nothing like just being on the ground in Israel to help you rekindle some of what make you fall in love with it in the first place, to reconnect with your answer to the question “Why Israel?” or contemplate a new, more nuanced one. And if a visit isn’t in the cards for right now, listen to a Hartman podcast, read a new book about Israel, educate yourself about an Israel perspective you’ve never considered.

May we be sealed for a New Year filled with good health and sweetness, with heartfelt and honest and even hard conversations, and hopefully even a trip soon back home to the Holy Land. Gmar Chatimah Tovah.